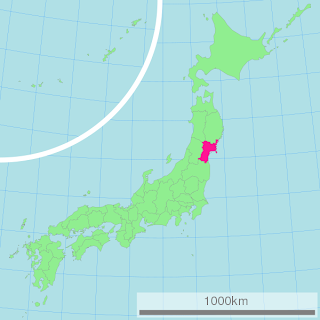

The Mutsu (陸奥 ムツ) originated across the Pacific in Japan, at the Aomori Apple Experimental Station. It is a cross between the Golden Delicious and the Indo, a seedling of the White Winter Pearmain, which is grown primary in Japan and China. The Mutsu was first cultivated in the 1930s, but did not receive it's name until almost two decades later. After being exported to England it was renamed the Crispin in 1968. However, in most places other than the British Isles, it is still known as Mutsu. The apple was named after the Mutsu province of Japan (see map), where it is believed to have first been grown.

Although I had heard the name several times, I was not properly introduced to the Mutsu until this past fall at Moose Hill. For most of the season the Mutsu held almost a mythical place in conversations about picking and bushel counts. If you were going to make that two hundred bushel day....it was going to be in the Mutsus. The Mutsu is a pickers delight; it has the right combination of good size and a firm flesh that does not bruise as easily as a Mac. When it does bruise however, the golden skin does little to deceive the flesh beneath. Any good apple picker knows that golden apples reveal bruises much more readily than their crimson counterparts.

Although I had heard the name several times, I was not properly introduced to the Mutsu until this past fall at Moose Hill. For most of the season the Mutsu held almost a mythical place in conversations about picking and bushel counts. If you were going to make that two hundred bushel day....it was going to be in the Mutsus. The Mutsu is a pickers delight; it has the right combination of good size and a firm flesh that does not bruise as easily as a Mac. When it does bruise however, the golden skin does little to deceive the flesh beneath. Any good apple picker knows that golden apples reveal bruises much more readily than their crimson counterparts. The Mutsu is one of the last apples to be picked, needing cold nights to sweeten and develop it's blushing cheek. Probably one of my favorite apples to eat while picking, one never goes hungry when there are Mutsus in the picking bucket; more than can be said for the Red Delicious. One of the Mutsu's downfalls, for the picker and grower alike, is it's tendency to bear a light crop the year after an especially heavy one. This was true for one of the blocks at Moose Hill, where some trees held less than a bushel of apples and a trip up the ladder felt hardly worth the energy expended.

Mutsu picking is often a good example of what pickers term "gravy." Everyone knows, but no one will actually talk about how good the picking is. There may even be secret accusations of gravy grabbing and you will rarely find anyone taking a break. In fact, it was a day in the Mutsu block at Moose Hill, the only day, when I and several others on the crew chose to take a lunch of Mutsu in the trees, entirely forgoing the hot food and cold water back at the bunkhouse, in order to try for that two hundred bushel day. I myself my have been called a gravy grabber that day, I have no shame in admitting it. At the end of the day however, walking past the long line of bins waiting to go back to the shed, a little humility goes a long way as you realize you and a crew of dedicated workers have helped bring in a magnificent harvest.

Mutsu picking is often a good example of what pickers term "gravy." Everyone knows, but no one will actually talk about how good the picking is. There may even be secret accusations of gravy grabbing and you will rarely find anyone taking a break. In fact, it was a day in the Mutsu block at Moose Hill, the only day, when I and several others on the crew chose to take a lunch of Mutsu in the trees, entirely forgoing the hot food and cold water back at the bunkhouse, in order to try for that two hundred bushel day. I myself my have been called a gravy grabber that day, I have no shame in admitting it. At the end of the day however, walking past the long line of bins waiting to go back to the shed, a little humility goes a long way as you realize you and a crew of dedicated workers have helped bring in a magnificent harvest.